New York — The corner is still there, but the man who made the album Bleecker and MacDougal is not. Fred Neil, he’s down in Florida, Coral Gables, Key West, somewhere. The San Remo Bar, its walls dark with the stain of Greenwich Village gossip and beatnik pipe smoke — it’s gone too. The Figaro, for years the coffeehouse catty-corner from the Remo, couldn’t take the Sixties’ exodus to home-based pot parties and closed. Gone is the Gaslight, where Kerouac read poetry to jazz, where countless, nameless folk-singers wailed under a lone, hot, yellow spot. The Cafe Wha?, where Jimi Hendrix played lead while Richard Pryor tried for laughs between sets, reopened briefly a year and a half ago. Now it’s closed too. Ditto the Cafe Au Go Go, home to Tim Hardin, the Grateful Dead, Odetta, others. The basements along MacDougal Street have been taken over by Middle Eastern restaurants and handmade jewelry stores. Bleecker is dominated by gypsy fortune tellers and Indian sleaze shops with brass hookahs in the windows. The neighborhood has been overrun by aging Sixties acid casualties panhandling for a pint of Wild Irish Rose with which to wash down their methadone tabs.

And so, when Bob Dylan returned to the Village about two months ago, people here sat up and took notice. Now it’s got to be understood that Dylan is in and out of New York all the time and people in the Village aren’t exactly moved to autograph-hunting frenzy by the news that he stopped in a neighborhood bar the night before. But this time was different. The city was collapsing, fiscally and physically, and Bob Dylan decided to come back? Now that was news.

For quite a while it has seemed as if a last beacon of hope had dimmed out, the Bleecker and MacDougal scene was finished. All movement in the city has been uptown, away from the Village. This year the gays dominated the club scene with places like Reno Sweeney, where Barbra Streisand lookalikes (male and female) sing smokey ballads and people primp and parade in ice cream outfits under lighting that makes everybody a star. The discos were drawing the crowds and live music had pretty much moved out of town. By last winter, it had become necessary to journey to the suburbs if you wanted to hear music that did not sound like it had recently escaped from a Broadway show that had closed after two nights.

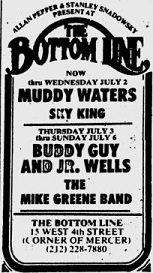

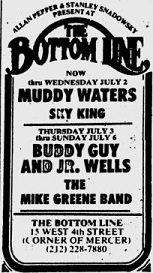

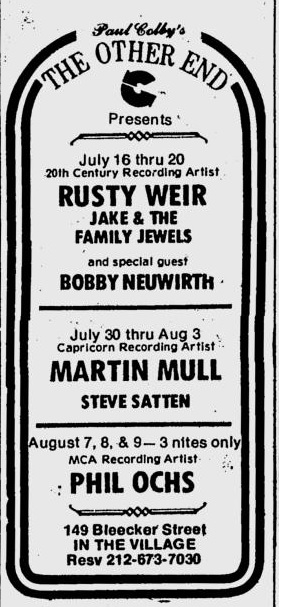

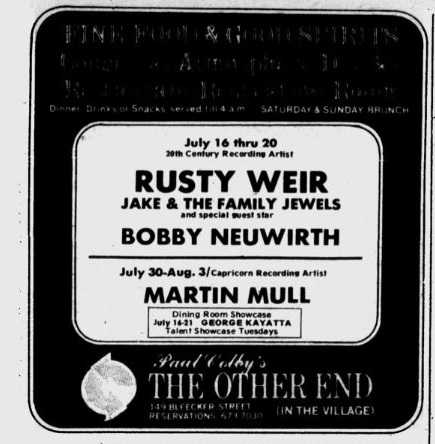

In June, the old Bitter End, closed for about a year, reopened with a liquor license. Owned by Paul Colby, one of the original partners, rechristened the Other End, it was attached to a bar and restaurant next door. It wasn’t long before you could see Dylan on the street, shuffling along in Levi’s and a black leather jacket over a striped T-shirt, his head of tight brown curls bopping up and down, a guitar case in one hand, a sheaf of papers and notebooks in the other. For several weeks in the South Village, it seemed like Dylan was everywhere, walking the streets, hanging out late. One night he showed up at the Bottom Line and played harp with Muddy Waters. A few nights later he dragged friends of his to see Buddy Guy twice. But it wasn’t until Dylan started hanging out at the Other End that the word finally spread: Dylan was back in town for the usual reason — his love for the energy of the city.

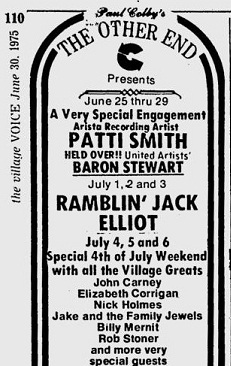

Dylan stopped by to see Patti Smith, the 28-year-old rock poet who looks like Keith Richards and sings like . . . well, like Patti Smith. She was packing the Other End every night with the cult-like following she has built up over the past couple years. Patti Smith stood defiantly onstage and threw challenges Dylan’s way all night. Stuff like, “Don’t you go near my parking meter, Jack.” Dylan grinned, then went backstage after the late set.

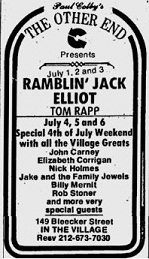

When Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, no stranger to the scene, opened on July 1st, Dylan was there. Jack, alone on guitar, sang “House of the Rising Sun,” “Tom Joad” and “South Coast.” Occasionally he left the stage and wandered through the audience, singing like a minstrel. Rosalie Sorrels harmonized on a few verses of “Tom Joad.” Dylan simply smiled while Jack sang “I Threw It All Away.” Around midnight, everyone went next door and drank until closing. Dylan ordered white wine, Jack Elliott drank tequila. A staggeringly drunk Phil Ochs stopped by and yelled at Dylan for a few moments. Dylan didn’t seem to mind. Bobby Neuwirth, a guitarist and longtime Dylan friend who is rapidly becoming known as the Don Rickles of rock, popped in and started rapping in his customary mile-a-minute way. Logan English, who was singing in Village bars when Bob Dylan was still trying to pass senior math, sat down quietly.

“That you, Logan?” Dylan asked sleepily. “Yeah Bobby, it’s me,” said English. “Hey man, I thought you were dead,” said Dylan. “I’ve heard the same about you a few times,” English replied. They both laughed.

“This is like a reunion!” someone yelled as Paul Colby pushed everyone out the door at 4:00 a.m. “Let’s get everybody together tomorrow night.”

And so they did. Ramblin’ Jack did half a set, then invited Dave Van Ronk onstage to sing “Salty Dog.” Neuwirth was lured up for one of his rare personal appearances. He sang a beautiful new truck driving song of his called “Cindy” and accompanied himself on guitar. (Rumor has it Dylan will record “Cindy” as a single.) Dylan came onstage and played rhythm guitar for Jack on one number, then he and Jack sang “Pretty Boy Floyd,” and Elliott stepped offstage. Dylan took the mike and, without hesitation, sang a song Neuwirth said Dylan had written that afternoon. Nobody knew the song’s name, but “Pleeese let me in your room one more time, before I disappear,” was the refrain. Dylan sang the song easily, with none of the gritty determination that characterized his singing while on tour last year. Though it was in the Blood on the Tracks vein, Dylan’s voice was closer to what you hear on Freewheelin’ or Another Side of Bob Dylan than on any of his recent albums. Then Logan English and Ramblin’ Jack sang “This Land Is Your Land” and the set was over.

Again everyone went next door and drank until dawn. While the room careened around him, Dylan sat in a corner silently, his watery blue eyes hooded by eyebrows that bobbed up and down as he listened. And listen he did, hardly saying a word all night. Several onlookers guessed that he was drunk, but as Neuwirth explained later, “He’s an audio voyeur. He’s like that every once in a while, just listening to and watching people.”

Early that morning out on Bleecker Street the crowd was breaking up. One groupie after another draped themselves about Dylan’s shoulders like dimestore scarves. One jumped in a cab and held the door for him; Dylan turned away. Another threw her arms around his neck and whispered in his ear. Dylan smiled and walked off. A third, hardcore uptown type, who looked like an unholy combination of a Times Square hooker and Princess Lee Radziwill and was known as Kitty, stuck to his side like cement. Finally Dylan said goodnight to everyone and wandered off down Bleecker Street in the direction of Sixth Avenue.

“Hey. Where’s he going?” asked Kitty. “He’s going for a walk around the Village,” Neuwirth answered. “That’s why he likes this place.”

A couple of nights later, Dylan played the Fourth of July hootenanny Colby held at the Other End. But it wasn’t until a week and a half later when Neuwirth put together a scraggly pickup band to play on the same bill with Texan Rusty Weir and locals Jake and the Family Jewels that anyone really got a taste of what Dylan has been up to these weeks in New York.

Neuwirth, ever the astute observer of the scene, sensed that something special was happening in the Village again. He got on the phone to friends on the West Coast, talked to Paul Colby, and in a few days had what he called a “house band” for the Other End, a nifty little outfit that could play with anybody who walked in the door. Each night, the Neuwirth band would play a few songs of its own, mostly country songs written by Neuwirth, Cindy Bullens or T-Bone Burnette, a Texas swing band leader from Los Angeles. Guest appearances were made by Garland Jeffreys, Patti Smith, Sandy Bull, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Eric Kaz, Loudon Wainwright, Murray Weinstock and Mick Ronson, the English rocker who found himself onstage for four nights running playing lead electric or acoustic rhythm guitar, depending on what equipment was available.

“Where is that goddamn English punk?” Neuwirth would demand from the stage, and the skinny Ronson would find his way to a guitar and an amp, plug in and deliver amazing licks while undergoing constant abuse from Neuwirth. Mate Ian Hunter sat alone against the wall in a T-shirt and shades. No one recognized him.

On opening night, Dylan made a perfunctory appearance to cheer on the Neuwirth band.

He watched Jake and the Family Jewels and the Neuwirth band’s set, then went next door. Neuwirth showed up with a couple of guitarists, Ramblin’ Jack and T-Bone sat in, and Dylan sang three of his new songs. One was the song previously mentioned. Another was “Isis,” an extraordinary, folky love song with a refrain that changed one word each verse, very much in the style of “Visions of Johanna” and the other songs for which he is best remembered, those from the bleak years, ’64-’65, from Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. Without stopping, he went straight into the “Ballad of Joey Gallo,” a ten-minute opus that had the whole bar singing along. Dylan threw his head back and laughed as he sang the refrain: “Joey! Jooooeeeeey! King of the streets, child of clay! What made them want to come and blow you away?” Later, Neuwirth, Ramblin’ Jack, T-Bone and others sang while Dylan played rhythm and harmonized. Nobody crowded around. Someone from Columbia said Dylan had recorded the three songs he sang plus one other. He said Dylan had been down to Trenton State Prison to visit Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the former boxer who’d been convicted of murder and is now appealing his conviction. Dylan wrote a song for him, too, as yet unrecorded.

“This is a very busy time for him [Dylan],” the Columbia man said. “He’s writing a lot, he’s recording and he’s looking for something new to get into. You get the feeling he really digs being back in New York. He’s looking into doing a show on Broadway, maybe a play. And he’s looking closely at TV, maybe a special. But most of all, after these nights down here at the Other End, he’d like to tour small clubs like this. There has been some talk of getting a van and driving around the country, dropping in, unannounced like tonight, playing a couple of nights and moving on. Nobody would know he was there until he showed up, so there wouldn’t be a crowd scene. And nobody would know where he would strike next. That’s what he wants to do most. Play bars, small clubs again. When was the last time something like this happened, Bob Dylan playing to a roomful of people, no microphones, no autograph hounds, no craziness? 1962? 1963? This has been good for him. And everybody up at Columbia is so excited! This new song, ‘Isis,’ they say it’s the best song he’s ever written, and after hearing him sing it tonight, I believe it.”

Talk of the resurgence of something akin to the old Bleecker and MacDougal scene has grown, but interestingly, it hasn’t centered on Dylan, despite the fact that the whole Village knows he’s back in town and writing like he did in the early Sixties again. Most of the talk is about Patti Smith, whose act can’t be categorized. She sings her own rock poetry, folk poetry and interpretations of oldies with various insane kickers and surprises thrown in. She recently signed a $100,000 contract with Arista, and expects to go into the studio in a few weeks. Close on her heels is Jake and the Family Jewels. Led by Alan “Jake” Jacobs of the Fugs and Bunky and Jake in the Sixties, the Family Jewels are a tight little band that plays a quirky, uptempo assemblage of oddball material, most of it original, all of it funny as hell. The “Jakettes,” Diana May and Kathy Whelan, sing harmony on Jake’s songs and solo on hot disco hits like “Shame, Shame, Shame.” Their novelty numbers — complete with production choreography and four-part harmony — had the crowd at the Other End splitting its sides. “This is the hottest band in New York City,” Neuwirth screamed above the din one night. “Any label that doesn’t want to sign them right away is out of its mind.”

As usual in New York, one hip, cynical “rock critic” noted that the innocence which complemented the folk scene in its heyday is no longer with us, and called the scene at the Other End a short-lived vacation from the serious business of making music these days. But those onstage saw things differently.

“This was special, sure,” said Cindy Bullens, best known in L.A. as the head Sex-O-Lette on the Bob Crewe-produced Disco Tex album, and for her sessionwork with Rod Stewart and Don Everly. “But nobody’s going to forget it. It’s the most incredible thing any of us have been involved in for years. Everybody has had such a good time, it’s got to continue to happen. Nobody wants to let this scene go.”

Neuwirth, the catalyst of the week’s activities, tried to play it cool, but five nights of madness at the Other End had penetrated even his thick veneer of hip. All week he kept asking from the stage, “Getting your four dollars’ worth? This enough for you? So what if we’ve only been together for 29 minutes. We got Mick Ronson and we are tight.” Late one night Neuwirth admitted: “Look, in a way this week was a tease. Everybody figured because I’m on the bill, Dylan’s going to play. But what’s really happening is this: Musicians want to get back in the clubs and hang out. Everybody’s tired of the concert scene. So we got Loudon singing three of his new songs. We got Kaz singing ‘Love Has No Pride,’ one of my all-time favorites. Where else are you going to hear Mick Ronson picking lead on an Ernest Tubbs song sung by Larry Poons, the world’s greatest abstract painter? Or Ramblin’ Jack do-wopping and yodeling while Patti Smith sings, ‘You cheated, you lied’ around a poem about King Faisal’s nephew? New York has got it. This is the hippest city in the country and the Other End is the best club for musicians since the days we used to close the Gaslight.”

Needless to say, Paul Colby agreed. “I’m going to start charging four bucks to get onstage,” he claimed at the end of a busy, crazy week. “At this rate, I’ll make more money that way.”